This history was part of the Barnegat Light Yacht Club website. While the website has since disappeared the history as presented on that site is as follows……

By Robert W. Kent

In the 1920s, the beaches at Harvey Cedars stretched hundreds of yards from the dunes to the sea. The sands met the bay at the waters’ edge because bulkheads had not yet been built to encase the lands of their owners into a manageable plot. The fire company still consisted of a two wheel cart carrying a hose which had to be pulled by hand or by car to the site of a conflagration with the hope that a hydrant was nearby. Electricity had just been installed. Not only had the Boulevard been newly paved, but many of the side streets reaching from the Ocean to the Bay had been improved to accommodate the growing number of residents. Public water had just been installed and the mosquitoes were absolutely terrible – a curse that had been brought by nature in the dark distant past and would stay until the 1950s.

Dr. E. Howell Smith, professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dentistry, and a resident of Harvev Cedars in the house at 78th Street and the Bay which still stands today with its balconies and gingerbread, called together some of his friends who also lived on the cove. The first meeting was held at his home in 1928 and then the group which numbered up to 24 would meet from time to time in the homes of the others interested in forming the High Point Yacht Club. The names of A. Ernest D’Ambley, J.C. Van Horn, Ralph Nash, J.B. Kinsey, Fred P. Small, Victor J. Stephens and Earl Hortter appear among the early records of the Club. Also among the original members were William Sloane, Ralph Charlton, Merritt Bigelow, Arthur Munn, Harvey Jones and Louis Wild.

Dr. E. Howell Smith, professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dentistry, and a resident of Harvev Cedars in the house at 78th Street and the Bay which still stands today with its balconies and gingerbread, called together some of his friends who also lived on the cove. The first meeting was held at his home in 1928 and then the group which numbered up to 24 would meet from time to time in the homes of the others interested in forming the High Point Yacht Club. The names of A. Ernest D’Ambley, J.C. Van Horn, Ralph Nash, J.B. Kinsey, Fred P. Small, Victor J. Stephens and Earl Hortter appear among the early records of the Club. Also among the original members were William Sloane, Ralph Charlton, Merritt Bigelow, Arthur Munn, Harvey Jones and Louis Wild.

The club began as a meeting in a local home in 1928. The High Point Yacht Club was formed at this original meeting and within a few years the members has purchased the current club property for $2000. A building was commissioned and built, which is the structure that is still found there today. The name was changed to Barnegat Light Yacht Club in 1932. While it may seem odd to name the club after the more northerly town, Barnegat Light was actually named Barnegat City during that time (the town name was changed in the 1950’s).

Two years later the group purchased a piece of ground from William Sloane who owned all of the land from the ocean to the bay between 76th and 75th Streets. They paid $2,000 for the lots that now hold the Club House and authorized John Gustafson to build the structure which stands today. He charged the members who, according to their By- Laws had to be male and 21, $6,000 to build, wire and finish the structure. The price did not include a bulkhead and for the first seasons the members placed their boats in the water in the traditional method of sliding them into the sea. It would be fifteen years until the first davit and hoist were constructed.

The Club was built for projected expansion of members to a capacity of 40 families. The barroom was to come later and dues were set at $25 with the obligation of new members who could afford this kind of financial commitment in the depression years. An enterprising member of the Club, who was also in the finance business, helped to organize a system that enabled qualified members to pay $5 down and the balance in easy monthly payments for the remainder of the year.

In 1932, Munn returned with the design for a flag and insignia incorporating these ideas and the Barnegat Light Yacht Club was born. It has remained so even through a brief legal contest when the borough at the Northern end of the Island changed its name from Barnegat City to Barnegat Light in the 1950s and felt it inappropriate for a club bearing its name to be located in Harvey Cedars.

The early Annual Meetings of the Club were held in January at the Walt Whitman Hotel in Camden. Here the officers for the coming year were elected and the men and women would have a mid-Winter get together. From these sessions came such decisions as the hiring of “John” the first Club Steward. In 1932 he was paid $5 a week. The next year at the same meeting the position was abolished. Two years later the idea was reinstated with the addition of a janitor; two years later they were dropped. And so it went.

In the middle-30s there was a feeling that the Club had to expand and a “taproom” added. Sayre Ramsdell was the Commodore and was told by the members that if that was what he really wanted, then he would have to raise the money himself. Not to be intimidated, and with the full facilities of the Philco Corporation and their entertainment accessories available to him, he staged a major social and show-business “bash” at the Germantown Cricket Club in Philadelphia. It raised more than the funds needed to construct the barroom that now occupies the northeast corner of the Club House. The addition was important because the Bamegat Light Yacht Club in the 30s predominantly was a social club. There was a handicap race every Saturday for the people with boats. There was never enough of one type of craft to run a class race until much later.

Saturday night was “party night” from July 4th until Labor Day. A band was hired for the big evenings at each end of the season. The women took turns preparing the dinners each Saturday night. There were thirty members involved. During most of the weekends Frank Smith would play the piano and there would be singalongs. For the more adventurous there were three slot machines whose proceeds helped pay off the mortgage on the building and the loan on the dock. The machines were sold in 1937 but may still be found in the homes of some of today’s members. Dinners cost $2 for adults and half that for children – when they were invited. Alcoholic refreshments were limited to three bottles of whiskey, three bottles of gin and a jug each of Manhattans and Martinis per week. The only “mix” was water and when the Club’s offerings were finished, members would fall back on their lockers in the barroom for supplementary libations – a practice that existed until the end of the 1960s. Then lockers became less popular, club offerings became more plentiful, and mixers were accepted.

The Ladies Auxiiliary, which had raised a few thousand dollars and helped furnish the Club House, was abandoned in 1936 the same year the Annual Meeting of members was shifted from January to September. Dues were dropped. $5 that year to $20 and the first tensions started to appear between factions in the membership. Income and expenses on an annual basis showed a break-even point of $1,000. The income in 1936 of $1,300 would stand as a high point for another eight years. The factionalism continued to build; resignations were rife. Then came December 7, 1941.

The years during World War II were not easy. Most of the men were away. The dues were waived and voluntary contributions were accepted. Enough money was received to maintain the club and pay the mortgage, which was held by three of the members (at an annual rate of 4 percent). Lloyd Good, who held more than fifty percent of the notes, waived the interest during those hard times and in return the Club granted him a lifetime membership with no payment of dues. The records showed income in those years of $235 (1942), $304 (1943), $80 (1944) and $240 (1945). There was a $350 operating deficit for the four years. Even though there were no activities, flag officers were elected each year.

The dues were reinstated in 1946 as Victor Stephens took over as Commodore, and the spirit of harmony was restored to the membership. A second generation of members started to appear with the entrance into activity of Jim DeCeasare, Jr. and “Beau” Freeman. The youth of the Club in the new spirit of freedom following the War were included in the innovative Saturday dinners which cost each member $2.00 and still included liquor until the bottle of gin, the bottle of rye, and the pitchers of martinis and manhattans ran dry. The concept of the Summer Member was created so that the established members could have the opportunity to meet and know their prospective colleagues more familiarly. There was still a limit of thirty on the number of members, this having been set when the original by-laws were adopted. Through the end of the 1940s, the Club had between 20 and 25 who paid dues of $9 while their wives were taken on as Associates at another $9 and almost everybody rented a locker for another $7.

Some of the names of that era which appear in the various records of the Club and the memories of its members still are familiar to residents of the area. Early in the decade the Club paid Howard Baum $8 a night to act as bartender. Carl Sjostrom first joined the club in 1940. Reynolds Thomas and his predecessor as Mayor of Harvey Cedars, Joseph Yearly, were both members of the Club after the War. Charlie Anderson and then Harry Haines took a stint as caretaker for the Club House when Frank Smith wasn’t around as chairman of the House Committee. Frank E. LeNoir and his orchestra came down from Philadelphia for the sum of $28 to play for the Saturday night dinners with dancing, and the Club retained its position as “the other Yacht Club” on the Island sharing the honors with Little Egg Yacht Club in Beach Haven.

The Surf City Yacht Club made its appearance in the late 1940s and soon competition on the Bay developed between the newcomers and Barnegat Light. Comets and Moths would race flat out down the Bay and then back again. The club Comets ventured to the Little Egg Club in 1950 and many years later with Lightnings for the Down Bay Regatta.

Life in America in the 1950s was quiet and comfortable with Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower serving as rocks of stability with the pattern of equilibrium reflected on Long Beach Island. Life at the Yacht Club did not differ as Victor Stephens went out during the Summer to raise the American Flag at the Club each morning and returned in the evening to take it down. The members of the Club continued to meet every Saturday night for dinner with the price increasing by the end to $ 3 and drinks were included as long as the three bottles contained something to pour.

The Commodore was the hub of all of this activity. He sat at an octagonal table outside the taproom. From this vantagepoint each week he and his guests could survey all that occurred. After the dinners they would listen to The Jesters who came from Philadelphia to play; or, they could sing along with Frank Smith at the piano; and of course they could see when everybody left. The Commodore and his wife cleaned up at the end of every Saturday night; in time, the Hostess for the evening and her husband assumed this task sometimes with the voluntary help of Members’ children. At the end of the decade Grace Miller came upon the scene where she has remained as a pleasant addition through today.

Real estate taxes were still $200 in the 1950s. Liability insurance with limits of $50,000 per incident and $500,000 for more than one person were thought sufficient by most of the members, although one resigned because he felt that the limits should be higher. This spirit of conservation spread to the adoption of a resolution that rescinded two Honorary Life Memberships of widows of past commodores because of the general feeling that only men could be members. Membership grew to 30 by 1959.

It was a decade that saw Dr. J. Arthur Steitz admitted to membership in 1953 and Dr. Harrison Berry welcomed two years later. Both men were to serve as Commodores later in the decade bringing further growth and stability before they retired. In 1957 the original mortgage was finally paid off but the Club went right back into debt with members lending $3,500 for repairs and renovations with an interest rate of 4 percent. With the injection of new money a flagpole was purchased, a new davit was installed and a hoist purchased, the current T-pier was installed, and, a new roof placed in 1959.

The sailing program was still a hodge-podge during the fifties. During the decade members raced a large variety of boats and anywhere from ten to eighteen craft would gather near the Clubhouse pier on a Saturday afternoon for the handicap race. Stephens was the only one who understood the system and he was never questioned about the running or the results. The starter’s cannon would sound and the Dusters, Cats, Stars, Comets and Moths would take off on a course that usually took them around Sandy Island with the blinker near the Bible Conference as one mark and buoy 82 as the other. Not only were there problems with the air but there was also the hazard of Races would last as long as three hours with weekly prizes awaiting the winners. These would include such esoteric items as a crab net or a paddle or an anchor for the boat eventually adjudged the first place finisher. Mary Thompson in her “Half Dollar” was the reliable crashboat captain.

One of the reasons for the high number of participants with a relatively small number of members was the standing invitation to non-members to enter. It was part of the Club’s involvement with the Community which spread to the usage of the premises for a fundraiser for the Island Library, a forerunner of events two decades later on behalf of the Southern Ocean County Hospital. Developing at this time, too, was competition among the teenagers and planned races for them began in 1956. As local interest spread and a desire for participation in interclub races resurfaced an Intermediate Membership category was established to permit our “members” to travel and let people know that Barnegat Light Yacht Club was committed to sailing.

By the end of the 1950s the new By-Laws of 1954 had taken hold and would govern the Club’s operations for a decade and a half. At this time, too, the concept of the Member’s Dinner, which started as a surprise going-away party for George Van Houghton upon the completion of his term as Commodore in 1950; took root. . It would blossom into the most warm and meaningful social gathering of the members and their spouses during the year.

Many of the movements that had their beginnings in the 1950s began to take shape in the early 1960s and assumed the form, which had been refined over the last two decades. Starting with the year that Art Steitz was Commodore the sailing program began to assume important status in the Club’s reason for existence. As a control and a very important source of revenue, charges were initiated for the storage of boats on the bay property. The members started to moan about the late starting time of the races and the three dozen members decided to open up the sailing to non-members and the membership to whatever limits necessary.

There were weekly races for the Lightnings whose numbers increased to ten during the decade. The junior members raced El Toros for a while and then made the transition into Sailfish and eventually Sunfish. But there were still enough other kinds of boats to retain the handicap races until the end of the 1970s. The enthusiasm for sailing spread outside the dock area at the foot of 76th Street. The Club hosted the Central Atlantic Division Lightning Races one year in the waters off Barnegat on the Mainland. This spirit of cameraderie grew into the first interclub reception with Surf City Yacht Club in 1969 coordinated by Oliver Goldman, Andrew Krecicki and Peter Metz.

The youth of the Club, the members’ children, were also becoming a focal point of interest. After putting off an organized program for thirty years and letting the children come to Saturday night dinner for a dollar each, a series of youth races saw the door of opportunity opened a crack. A beach party was the next step. Finally, in the midst of the 60’s with the world in torment, a one-month formal youth program was established and thirty attended. It was able to sustain itself and soon there were swimming programs for the youths and by the end of the decade there were pre-teens and teenagers in classes for swimming and sailing instruction in Lightnings and Sunfish.

With growth in membership and the introduction of younger members with new ideas the Club became a mix of the traditional and the changing fashions. One could still see Sam Freeman and Alf Melander debating the fine points of the Greek and Roman poets – in their original tongue. The leadership decided that the mortgage on the Club had been carried long enough and retired the debt and did away with the shares that gave one the feeling of a proprietary interest. The number of dinners declined during the decade as new opportunities for entertainment appeared on the Island. Insurance liability coverage .vas increased to the $100,000 – $300,000 level to give comfort to those afraid of litigation. Also, dinners were starting to cost $3.00 each and the members were starting to grumble Dues would go to $50 by 1969.

F. Morse Archer and Dick Angell became members and intermediate members respectively in the early 1960s. During the decade they were followed by Bill Collier and Bob Bent (1962, George Forsman (1965), and Dor Haight (1966). The telephone was installed for “a two year trial”; a long-range planning committee was established to examine the feasability of enclosing the porch and extending the bulkhead; and Mayor Thomas said that a portion of the adjoining Borough ground could be used for sailfish storage One member resigned because he said, “I am now engaged in raising chrysanthemums on a large scale and it takes up most of my time.” It was a busy time for the Club, free of the turbulence that was racking the world around it.

The writer of the next history of the Barnegat Light Yacht Club will be able to place the Seventies into a better perspective with the benefit of hindsight. At this time a review of those years will show further refinements of the initiative of the Sixties and a building upon and continuation of the base of those programs.

The hoist and the flagpole that now stand by the bay were the products of the Seventies. The family of Victor Stephens, upon his death, created an endowment ensuring funds for the purchase of American and Club Flags, in his memory. The case for the Flags was built by Frank Smith and Vic’s picture sits on top as a memorial. A Club lightning was purchased. A Moth and a Penguin were received. A flood of sailboats, Lightnings and Sunfish overflowed the area available for storage and spread to the neighboring ground. Oliver Goldman introduced the name badges in 1973 as membership started to grow. The number of active members reached a high of 70 in 1979.

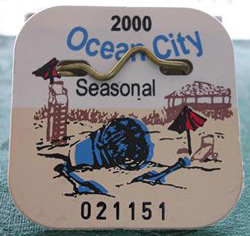

An interesting aspect of the passing of borough by borough beach badge ordinances is the regularity of the same kind of process unfolding in many different places. First the town officials come up with a plan to sell beach badges and this idea in turn has to be “sold” to the residents. Town managers clearly realize the added revenue from beach badges can be a big boon to the local budget. Residents on the other hand are reluctant to begin to pay for something that they had been getting for free. Once an ordinance is passed and begins to take effect there is a period where some people that use the beach are angry and, in some cases, take their case to court. The defendant argues for unencoumbered beach access and the cases are always decided in favor of the municipality.

An interesting aspect of the passing of borough by borough beach badge ordinances is the regularity of the same kind of process unfolding in many different places. First the town officials come up with a plan to sell beach badges and this idea in turn has to be “sold” to the residents. Town managers clearly realize the added revenue from beach badges can be a big boon to the local budget. Residents on the other hand are reluctant to begin to pay for something that they had been getting for free. Once an ordinance is passed and begins to take effect there is a period where some people that use the beach are angry and, in some cases, take their case to court. The defendant argues for unencoumbered beach access and the cases are always decided in favor of the municipality.